HOPE worldwide Volunteer Corps

Mutuality. Partnership. Relationships across cultures and languages. Learning from one another with humility and respect. All those core values are exemplified by our teams of volunteers. Dr. Chris Kafka and his daughter Mackenzie, from Kansas City, served on the Nepal August 2019 Volunteer Corps. Dr. Kafka is a family physician with many years of experience. We often have a small group of medical professionals on Volunteer Corps. The Nepal trip had a few nurses, two dentists, and a family doctor, Dr. Kafka. They teamed up with local practitioners and worked side by side, learning from one another, exchanging best practices, and becoming fast friends.

My experience in South Africa was incredible and impactful. On my first day back, all my co-workers bombarded me with questions like: “Well!? How was it? Did you have fun? Did you take pictures?” To which I would smile at them, mentally ask myself, “How do I explain to them that my trip was good, but not the ‘good’ they’re asking?” And eventually I would shrug and say, “Yeah, it was good.” As the days have passed, “yeah, it was good” has expanded to in-depth discussions on what I experienced and learned. One thing I learned was that these kids weren’t broken. I arrived at the creche with my crew and expected the worst—worn-down materials, children without shoes, and a feeling of despair. That was not what I found at all. What I found and experienced was exuberant joy in the form of jumping, laughing, screaming children, whose eyes just glittered with a spirit of play. I was taken aback, and completely thrown off. Where was this vision I was expecting? I grew troubled and uncomfortable. I didn’t come here to work with...with...with preschoolers!? I came to work with children who were down in the dumps and less than me. Soon enough, that feeling of despair came, but it ended up emitting from me, go figure. After another day at the creche passed with me trying to figure out how the child in front of me was still joyful, despite the fact that we had just spent the last ten minutes unsuccessfully trying to count to four. It eventually dawned on me after that day. I went into South Africa with the desire to “fix” these children...but when I really looked at it, what about them was I trying to fix? What was so flawed about them, that I chose to overlook the joy and laughter all around me. These precious, lovely children were just like the children back home. I could switch them out with kids from my school, and they’d do just as well. These kids didn’t want my fixing. They wanted my love and attention. They wanted my laughter and my joy. If they danced, they wanted me to dance. They wanted to hold my hand. Yes, learning to count to three is important, but that comes with time, and with an effort that will take longer than a week. And like that, the pressure was lifted. Instead of a broken vessel, what was in front of me was a child who needed to be loved, nurtured, and enjoyed. I’m so grateful for this experience because it taught me that the great things we do are caused by love, and that, at times, the greatest and the only thing we are asked to do is simply love. Yeah...it was good Do you want to experience love like this? Well, you can. Check out our amazing 2020 Volunteer Corps programs today. hopeww.org/hvc

Seventy motivated individuals set out to serve for two weeks in Daanbantayan, three hours north of Cebu, Philippines. We were to spend Christmas and New Year in a community devastated by Typhoon Haiyan six years ago. After that typhoon, HOPE worldwide Philippines built a Center of HOPE to meet the needs of the community and help rebuild.

The 2019 HOPE worldwide Volunteer Corps to the Philippines has changed its focus. Typhoon Ursula made landfall near Daanbantayan on Christmas Eve. The team of 60 international and 10 local volunteers spent the night sheltering in the Center of HOPE in Daanbantayan. All of the participants are safe as are the disciples in the International Church of Christ congregations in the area.

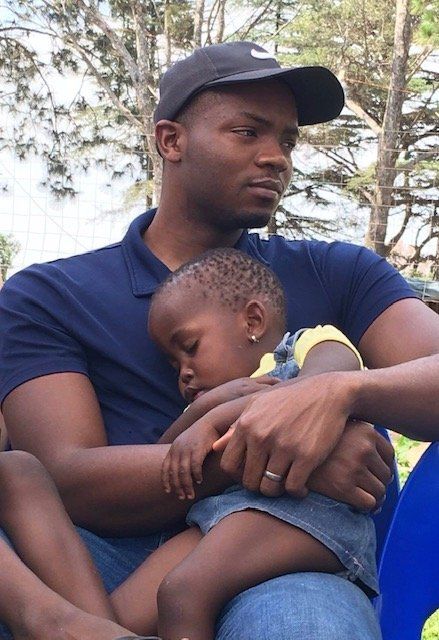

If a picture is worth a thousand words, what are the stories they tell worth? Since the beginning of human history, stories have been a way to communicate and share ideas with one another that transcend geographical barriers. There is a true power in the stories that we tell because it paints a vivid picture in our minds and helps to ignite an instant connection. Stories can be uplifting, cautionary, entertaining, damaging, etc. We see it in society: The stories that we hear influence our opinions; they make us draw conclusions, show partiality, help us gain a new perspective and so much more. The stories that we pass on through generations fill up history books, some shape culture, and some are embedded in the values that we keep. Today, I want to share with you the power of the stories that we tell, through my story. I was born in Osun State, Nigeria and like most kids my age (8), I had this grand vision of what it would be like to live in America. When I thought of America, my understanding came from the characters that I watched on television and stories that I heard from people. I grew up watching Power Rangers, so my expectation was that there were men and women in colorful tights running around fighting monsters daily. Through movies, I had a vision that all Americans were wealthy, lived action-filled lives, and were very self-focused. There was a mixed portrayal on television that made it difficult to understand the typical American, but I knew I wanted so desperately to visit this place to see all the things that I had heard about. In 1999 my family moved from Nigeria to Atlanta, Georgia. Needless to say, I was very disappointed upon my arrival. Most Americans lived very mundane lives; outside of culture, language, and geographical differences, their lives were very similar to mine. The biggest disappointment, though, was that there were no Power Rangers running around to save the day from monsters. My expectations were crushed. I realized that even though some of the things I saw on television were accurate, most were completely dramatized or inaccurate. If I did not have the firsthand experience of moving to America, I would not have known how untrue these depictions on television were. Even though I came to realize that I wasn’t very different from most Americans, it didn’t take long for me to realize that there were expectations of me as a Nigerian. As I started school, it seemed as if my attendance at school was a big feat that I had undertaken. I was in the school announcements and articles; it seemed like news that people had been anticipating for a long time. There was some sort of celebrity that came with the fact that I was there and that I was from Nigeria. Once I began talking to my classmates, I was met with questions like, “Did you live in a hut?” “Did you have a lion as a pet?” “Did your family walk from Africa?” “Did your family escape from war?” and my favorite question, “Is Nelson Mandela your dad?” I say that it was my favorite question because I may or may not have encouraged the rumor that I was in fact Nelson Mandela’s son, but that is a story for another day. I was perplexed and became overwhelmed with the amount of attention I was receiving and the amount of questions being asked of me. As the questions poured in, I began to realize that my classmates saw me through one perspective, one as a poverty stricken, unschooled, pitiful African. Their questions became increasingly hurtful and demeaning. “How did you learn to speak English?” as if I were not capable of learning; “Do you have AIDS?” a question that made me an outcast amongst other students; “How can you afford to live here?” as if my being Nigerian meant that my family depended on handouts. It became difficult to want to wake up and subject myself to the daily questioning, so I just began to retreat from interactions and allowed the stories to perpetuate, feeling helpless, as if my story didn’t matter. At a very young age, I began to realize and understand the power of the stories we tell. Before my classmates got a chance to know me, they already knew me, or at least they knew the African that they had heard so many stories about. I began to see where the misinformation came from when I came across representations of Africans in media. It was through infomercials asking people to feed the poor hungry African child; it was through the dark-skinned character with a thick accent that lived in a fantasy jungle amongst animals; it was through the foreign family that needed help to overcome adversity with the help of American counterparts. I began to feel as if I was categorized..if I was from Africa, these stories had to be true about me. That I was a poor kid, from a poor country, with no education, and no means for his family to provide for themselves. That was who I was in their eyes, that was my story. In the story that had been constructed for me, there was no hope of me being different than what was expected. Is there poverty in Nigeria? Yes. Were there people dependent on the kindness of a stranger to eat? Yes. Is there political turmoil? Yes. Were people dying of diseases? Yes. Although true, this was not my story. It was also not the complete story of Africans, as it is not the story of many American people who face similar afflictions. These were general depictions of Africa that highlighted the most negative aspects of the continent and gave it a character that completely disregarded that there are 54-plus countries with different cultures. It disregards the love, joy, family, friendship, innovation, brilliance, ingenuity, simplicity, and resilience of the people that resided on this continent and summed it up in one story..a story of poverty, neediness, barbarism, underdevelopment, and inferiority that has shaped the view of Africans internationally. Even now, many of us unwittingly do this. I want to use the example of international mission/volunteer programs. When you hear someone share about their time serving in a different country, you typically hear stories of the poor people they encountered, the pity they felt, how they were able to help, and the gratitude they feel for the lives that they have in comparison. Please, do not take this as a criticism of people with good hearts; it is quite the opposite. While I applaud the volunteerism and the desire of people to help those in need, I want to make sure that we have the right perspective when we enter a moment in someone’s life so that we do not go on perpetuating untrue stories. Here is an example to give an idea of what I mean. Think of the most vulnerable moment in your life, maybe you were fired from a job, had a family death, were dealing with mental or emotional health issues, whatever that moment was, I want you to remember how you felt. Now, insert a stranger that wants to help. They come in for a few weeks, show you sympathy, serve you, share stories with you, take a couple pictures, then they leave, never to be heard from again. The story that they leave with is “Poor John, he doesn’t have a job, but I helped him get food to eat”. “Poor Susie, she is having family problems, I feel bad for her because I have a strong family, but I was able to give her some good advice.” When they share about their time with you, they speak of you through your vulnerable moment. They perpetuate the story of your ailment amongst their friends, on social media, and in large groups. This is the story that is spread without your knowledge, but it informs people on who you are. That is the power of a story, a single negative moment in your life being taken as the totality of who you are, neglecting other aspects of your life and going on to shape how people view and interact with you. The power of the impact that we make when we serve others is maximized or minimized by the stories that we tell after. There is so much more I can say, but I will end with this: We all have biases or false stories that we perpetuate about people or places because of our lack of exposure and understanding. Again, my story is not a criticism meant to minimize the impact of the amazing volunteer work that has occurred across the globe; this is simply my perspective as a Nigerian living in America. To this day, as an adult, I still face the challenge of re-writing my story. There are deeply ingrained stories that people hold on to that make it difficult for them to have a new perspective. I can feel weary of wearing my traditional Nigerian clothing amongst the general population because I grow tired of hearing things such as “Those look like pajamas,” “Did you get that from Wakanda?”Granted, I don’t think anyone meant to be spiteful in their comments, but when we grow accustomed to being cavalier with our speech and showing a lack of consideration for those around us from a different culture, we alienate an entire group of people and disregard their story. I want to challenge our single-minded stories and want us to ask ourselves why we believe the stories that we believe. Stories have been used to malign, but they can also be used to empower. Stories can break a people’s dignity but can also heal. When we reject these incomplete stories, we embrace a new perspective that gives people an opportunity to be themselves. That is why I believe that we must all do our part in recognizing the plight of people around the world struggling to change the stories that have been written for them. To do this, I believe we must first address our own biases. We must learn to look inwardly and examine if we truly live a life that celebrates our own culture but seeks to understand the culture of others. In my life, I have appreciated people who have chosen to be vulnerable and expose their prejudices. Their search for understanding and their desire for growth has been an inspiration to me. I am aware of the complexities that come with embracing cultural understanding in an all-inclusive way; it seems ever changing with every person. While you may not do it perfectly, I commend your efforts. You are the ones that will impact the world and bring us closer as a global community. To you I give a final encouragement: My sadness is not my story. What is painful to me in the moment does not define who I am. The issues that plague my country is not the character of my people. We don’t need your pity, we don’t need your tears, we don’t need your political opinions; we need your support, we need your love, we need your understanding, and we need the power of your voice to tell our story.